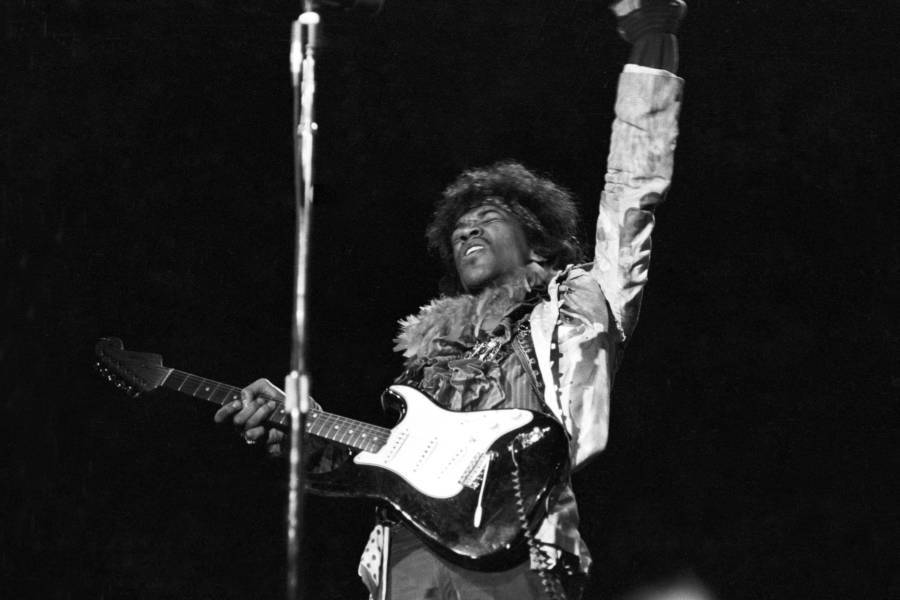

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been undertaking a study of Jimi Hendrix’s classic take on All Along The Watchtower with one of my students.

Initially, the study was only due to take a couple of weeks, but it provided so many interesting points of discussion between myself and my student that it mutated into a month-long, behemoth of a look at the song that we spread out over a period of 5 or so sessions.

Over this period of time, we used the concepts seen in Hendrix’s solos as a springboard into a number of other topics. Most namely, though, came Hendrix’s masterful way of storytelling through his solos and musical devices, all the way until the fiery, iconic climax that rounds out the piece.

Naturally, this got me thinking about how similar songwriting is to storytelling, and why a force so simple (yet so profound) as music can conjure up images of sweeping fields, or bustling cities, with only the power of sounds and lyrics. Hence today’s post.

So how can we use these concepts?

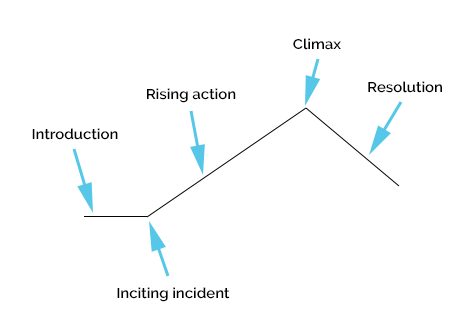

Each great narrative has a set of common elements that they share. Some deviate slightly, but these are largely similar between the vast majority of great stories throughout history.

Though it may seem unlikely at first glance, this narrative scaffolding can just as easily apply to your songwriting process. Thinking of songwriting as analogous to storyboarding/ drafting a film, book, or videogame can prove one of the biggest and best boons for your songwriting.

It provides direction and context to your discretion in choosing musical features, and – if done well – can allow you to craft pieces that extend beyond just music- into the realm of high art.

Let’s storyboard.

Orientation/introduction:

This is where the scene of the song is set, the key players are introduced, and the overarching tone of the story is provided. The introduction of a story serves an important chance to foreshadow the themes/events that’ll occur later on, including the climax and finale of your piece

Often, it can be of significant merit to open with an engaging ‘hook’- this could range from the presentation of a main riff/melody immediately, or an especially infectious fill/passage. Either way, a hook should – much like any great story – serve to capture and absorb the listener in the music instantaneously.

I like to think of the ‘setting’ introduced by the story as similar to an introduction of key/tonality in your song, with recurring motifs and ideas being the main ‘characters’ of the story.

Setting up key motifs and riffs that you plan to use throughout the remainder of your song can be seen as a means of musical foreshadowing. One of my favourite examples of this method is Dream Theater’s Octavarium. Give the introduction from 0:00 to 3:47 a listen, and challenge yourself to recognise the key motifs and features that appear later in the piece- all set up by this incredible introduction.

Inciting event

Also known as the ‘conflict’, the inciting event is the point in time (usually fairly early on in the story) in which a problem – one with no clear solution at this point – is presented. This problem must be gradually worked through as the story progresses.

This can be seen musically in what I like to call the ‘kick-in’- the moment when the rest of the band comes in, hitting the first chord, or when the first solo begins. Continuing with our examples of Watchtower and Octavarium, the inciting event(s) can be heard at 0:10 and 3:49, respectively, as Dream Theater ploughs through a massive chord, and Hendrix launches into his fiery solo.

The inciting event can also be expressed in your lyrics’. In Watchtower, Dylan’s original projects this conflict immediately:

There must be some kind of way out of here

Said the joker to the thief

And in Octavarium:

I never wanted to become someone like him so secure

Content to live each day just like the last

Immediately beginning your first verse with an explosive or engaging line is one of the best ways to communicate the key issues your song is going to tackle.

Rising Action

Also known as the ‘series of events’, the rising action of a narrative is generally the longest and largest section – both duration and volume of content-wise. It can include its own subplots, and generally has its own peaks and valleys in terms of intensity of events, though these peaks are generally less profound than the larger climax, and the valleys less deep than the interlude.

Musically, a songwriter’s ability to add variation and nuance to already-established riffs/ motifs is one of the critical traits in creating effective rising action. Layering different parts/rhythms/instruments can also add to the effectiveness of your rising action, though keep in mind that if you overdo your rising action sequence by inclusion of too many sections, you can easily back yourself into corner – making this section ineffective and difficult-to-follow.

One of the biggest risks here is avoiding monotony; keep in mind that you want your rising action to have its own sub-peaks and valleys: aim to have your complexity and tension look like the line graph projections of a company steadily growing. Throughout this section, it’s good to maintain a steady incline of tension, lest you risk your song sounding deflated and underwhelming.

Lyrically, here’s your chance for more of your plot exposition. One of the most useful techniques to making your series of events lyrically engaging is by using the 7 senses (sight, sound, touch taste, smell, bodily, kinaesthetic) as the basis for your lines and stanzas. By using sensory detail, you can create vivid imagery that will supercharge your ability to propel the song forward. (For more on sensory writing, check out Pat Pattison’s Writing Better Lyrics, a great guide that has a number of in-depth lessons on the topic).

In Watchtower, Hendrix uses the verses as a means of injecting continually intensifying complexity into his embellishment of chords, thus maintaining a general incline in terms of tension- building. Notice how well Dylan’s imagery and dialogue-based stanzas play into Hendrix’ music, making for an exciting series of events that proves engaging lyrically and musically.

Depending on how prog you want to get, these variations can expand into whole new sections, as Dream Theater does in their instrumental sections/ ‘sub-songs’. Notice that each of these internal pieces has their own highs and lows, yet all function to push the story forward, and keep its momentum at a consistently interesting level.

Interlude

One of the keys to effective storytelling is contrast and juxtaposition, and the exact same principle applies to the creation of music. Songs that ‘go hard’ for the entirety of their duration can easily become tired – even irritating – and even most ambient music pieces have their own variations to keep the piece from verging too close on monotony.

The interlude – most often seen before the climax of the narrative structure – could be likened to the ‘calm before the storm’ – a section of tranquility or variation before the song kicks into high gear.

This is most often expressed through the Middle Eight, Bridge, Solo, etc., in popular music – though both progressive and jazz music can see a marginal to drastic change in tempo, harmonic progression/ tonal centre, time signature – and in some cases – even a complete change of style/genre.

One of the biggest challenges with making your interlude effective is ensuring that it doesn’t feel forced or shoehorned in its inclusion. Stylistically, it should build upon – not detract – from the previous musical elements presented. However drastic of a change it happens to be, make sure that in some way, it bonds cohesively to other elements/motifs; make it feel at home.

Lyrically, the interlude is a great opportunity to give listeners a new take on the subjects previously presented, or to reveal the the ‘revelation’ that drives the music into its grand finale.

Examples can be seen in Octavarium- from 20:00 to 21:00, where the (relatively!) calm sectional deviation precedes what’s often called the ‘God Solo’ by Dream Theater fans (give it a listen and I’m sure you’ll agree). Watchtower’s interlude comes in the form of the slide, wah, and chordal solos from 2:00 to 2:49, after which the piece kicks into its incendiary final verse and solo.

Climax

Here’s where things get big.

The climax should represent the culmination of your story thus far- where all the elements constitute a musical whole that ideally outweighs the sum of its parts.

If you’ve been making use of motivic devices rhythmically, melodically, or harmonically throughout your piece, tying back to them here is a great way to drive home the impact of this section. An effective climax is, in a word:

Massive.

In classical music, a piece’s climax is often expressed through its cadenza, in which the primary instrumentalist will show off their virtuosic chops through an especially monumental solo-based section. This cadenza-type finale can be seen in Octavarium‘s climax, from 21:29 until its tension culminates in the bend at 23:00.

In Watchtower, this comes in the form of what’s regarded by many as the single greatest bend in rock music; at 3:39, Hendrix’s high C soars above the musical landscape for one of the most epic 20 seconds in musical history.

Resolution / Finale

Once all is said and done, the big finale of the piece has passed, and the dust has settled, it’s time to bring things to a close.

Musically, a piece will often end three ways:

- The ‘happy/expected’ ending: A song resolves to its home tonality, completing the cycle of tension introduced in the piece’s climax.

- The ‘deceptive/twist’ ending: This kind of resolution subverts the listener’s expectations; it may come through the inclusion of a deceptive cadence, or a final, unforeseen section preceding the close of the song.

- The ‘non-ending/unresolved’ ending: This can be easily achieved by hanging on the chord purposed to resolve to the tonic/root chord, creating a sense of tension and unease.

Tying back to the orientation of your musical story during the resolution helps bring the piece full-circle, especially terms of cohesion. Effective resolutions allow your music to transform from a simple collection of musical ideas into a unified, actualised whole.

The vast mass and gravity of Octavarium‘s collection of musical ideas sees it fit that it makes use of our first type of ending; the massive chordal hit that brings close to the piece also sees a recapitulation of its main motivic melody, much in the same vein of the cinematic film epics that it functions in equivalence to.

Watchtower‘s grand finale simply fades away; though its ending is much less pronounced and distinctive than Octavarium‘s, it proves just as thematically appropriate. As expressed in the lyrics, the ‘howling wind’ seems to carry this finale away with it – and despite having resolved on the root – maintains an element of suspense and uncertainty lyrically:

Outside in the cold distance

A wildcat did growl

Two riders were approaching

And the wind began to howl

These final lines of Dylan’s lyrics leave us on an ambiguous resolution that suggest there’s still more to come.

This week’s challenge: write a song in the context of an already-existing story

Using the events of a pre-existing book, film, or game as a prompt for the context of your own music is one of the most fun and exciting ways to come up with some of the best music you’ll create.

For one, it allows you to construct an overarching vision and purpose for the song, one of the most important elements when it comes to ensuring cohesion and direction.

Secondly, it gives you a basis for your musical choices when songwriting, and ensures that each musical device you employ is both purposeful and intentional.

It also gives you a clear structure for your story to follow; any great story has all of the aforementioned narrative elements; being able to express these clearly and purposefully will both challenge and expand your overall musicianship and songwriting capacity.

Indirection is one of the greatest enemies of great songwriting, but using the aforementioned principles wisely and tactfully will help to flush it out of your songwriting process. Give it a try and comment below how you found it.

A Final Word

Today we’ve looked at utilising narrative structure in context of single songs/pieces, though keep in mind that they can also apply on a micro scale – for use in shorter songs of ~4 minutes, to medium-scale: multi-movement pieces like Octavarium, to macro-scale, such as throughout whole concept albums.

Remember that all these concepts are simply suggestions to assist you in the process of songwriting, not rules set in stone. By all means, break these rules in any way you see fit, and interesting results are sure to follow.

And above all, remember that songwriting – just like any other craft, is the product of time and pressure, and using this philosophy takes time and effort. Don’t kick yourself if writing in this manner initially feels difficult or forced, and remember that you are always your worst critic; keep your head up and your eyes on each little victory.

Now go and write the best music you’ve ever written.

Want the Free Ultimate Prog Chord Compendium? Sign up below!

Further Reading

Pat Pattison – Writing Better Lyrics:

Adam Neely – Reharmonizing Hello