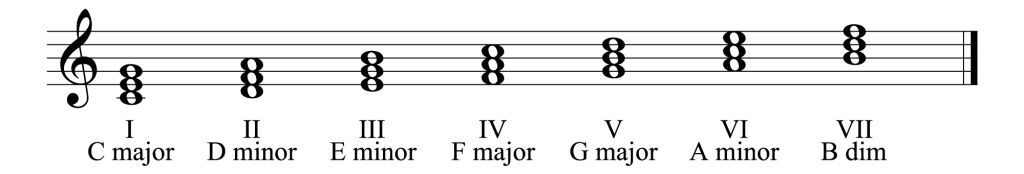

By now, you should know the order of diatonic chords in major and minor pretty well. Here’s a quick recap:

Major: I ii iii IV V vi viidim

Minor: i iidim III iv v (or V) VI VII (same order as major, just starting on vi).

All there, at your convenience. Easy enough, right?

Well, not exactly.

See, it’s all well and good to play and write music completely diatonically, but oftentimes, this method can come out sounding a little, well, bland.

Enter the mighty chord substitution!

In any key, there are always a litany of chords that you can use to spice up- or entirely transform- your progressions and compositions.

First off, what exactly are chord substitutions? There are 2 main types, these being:

1. Diatonic chord substitutions, i.e a chord that plays the same functional role as another chord in that key,

and

2. Non- diatonic chord substitutions i.e any chord substitution that is non-diatonic to the key (meaning it can’t be naturally built out of the notes of that scale).

Chord substitutions are most commonly used in functional harmony, though a number of substitutions are useful for ‘modal mixture’ & ‘modal interchange’- especially with non diatonic chord subs (more on that in a second).

Today, we’re going to just be looking at non-diatonic chord substitutions, as they can provide some of the more ‘vivid’ colours and visuals to your tunes.

Food For Thought

I like to think of chord substitutions as analogous to cooking a meal: A a few subtle chord substitutions for some spice and seasoning, or use a whole lot for a full on chilli con carne.

Though, beware. Use too many and you’ll spoil the broth with a bit of the ol’ atonality. Let’s get cooking.

Keep in mind this is by no means a comprehensive list, as there are essentially and unlimited bank of chord substitutions that you can pull from. These are simply a list of the most common and useful substitutions.

iv in Major

Using a minor iv in a major is one of the best and easiest ways to introduce emotion, anguish or solemness into a regular plagal (IV-I) cadence, by creating what’s commonly known as a ‘minor plagal cadence’. Especially useful after a major IV chord, the iv can musically accompany themes from unrequited love, to death and mourning. Radiohead’s No Surprises is a prime example of this, alternating between I and iv.

IV in minor

In minor, we also have the inverse. The use of a IV chord in a minor tonality is commonplace in classic rock and blues (among a litany of other styles), and evokes a Dorian tonality through its inclusion of the natural 6th. This is an easy way to brighten up your minor chord progressions, and bring a feeling of hope to the musical table. This can be especially useful as a transition to a V, adding a dash of Melodic Minor flavour. A great example of the i- IV comes in the verses of Electric Light Orchestra’s Mr. Blue Sky.

III in major

This soulful chord is a staple of Gospel and RnB, and one of the most straightforward ways to transition into your vi, or relative minor (in this case, the chord would be described as the V of vi). The chord can also be used to transition up a half step to your IV, giving a Lydian tendency to the resolution that can help establish a dreamy and uplifting feel to your progression; an example can be seen in Pink Floyd’s Nobody Home at 0:35.

bV/#IV in minor

Known as the ‘tritone chord’ this chord away from the root is like the musical equivalent of adding a ghost pepper into the musical mix. One of the most evil-sounding transitions can come through the use of this chord. As part of a #IV to V, this chord can create a dastardly- sounding chord cycle in minor keys, especially useful for neoclassical pieces. You can find this chord in a number of tunes by Yngwie Malmsteen, and his neoclassical contemporaries (Paul Gilbert, Michael Angelo Batio, etc.)

bVI/bVII in major

These chords-often used in conjunction with each other- are borrowed from the parallel Aeolian (natural minor) scale (e.g Ab major and Bb major in the key of C major are both borrowed from C Aeolian). Using these in a bVI-bVII-I progression can create a massively impactful resolution back to the I, often described as a ‘backdoor resolution’. Some examples of this cadence can be seen in Dream Theater’s To Live Forever (see if you can spot it), as well as the flagpole victory theme in Super Mario. These chords contribute to a grand, victorious-sounding resolution that can add huge punch to the end of a piece.

bVI7 in minor

This chord is one of the best ways to make your V-i in minor flow more smoothly and effectively, through its use of the ‘tritone substitution’ – alternatively known in classical music circles as the ‘augmented 6th’ chord. Especially useful after the bVII in minor, in transitioning to V-i, this whole progression (i-bVII-bVI7-V-i), is what’s known as the ‘Andalusian cadence’ a staple of ethnic Spanish and Flamenco music. This is one of the better ways to add an exotic Spanish flavour to your songs, essentially adding jalapeños to your musical dish. One of the most profound examples can be seen in Al DiMeola’s Mediterranean Sundance, where it sets up a classic and iconic resolution back to the i.

bII in major or minor

You’ll often see this described as a ‘neapolitan chord’ in circumstances which it precedes the V. Borrowed from the parallel phrygian mode, the bII can be used in a similar manner to the #VI/bV: a massively destabilising and evil-sounding chord, especially useful in metal, or preceding the V, as the bII is a tritone away from the V. This chord can alternatively be used as a ‘lift’ in progressions, to bring newfound vigour and life to your songs, and is a veritable swiss army knife when it comes to modulations. Metallica’s One is a key example of this substitution, though its more beautiful side can be seen in the intro to Floyd’s The Great Gig in The Sky.

Spoiled for choice

So, which of these ingredients do we choose to add to our dishes? Choosing them all can very well result in an over-indulgent and sickly dish.

The key here is context. What you want here is to consider the overall vision for the piece: what you want it to convey, and what story you want your song to tell. These in mind, your chords should help support this vision, and convey the emotions and visuals that come with it.

Something to watch out for

You should also keep your melody in mind. Whatever chords you sub in, you want to make sure they don’t clash (i.e have notes a minor 2nd or tritone) away from the melody line. Though, this does ultimately depend on the overall vision you have for the piece, and if you are wanting to include dissonances and clashes in your songs, by all means, go for it.

And now there’s only one thing left to do.

Get writing!

Want the Free Ultimate Prog Chord Compendium? Just sign up below!